“Here, you take it,” Jonathan Frid said, handing me a VHS

tape. “I’m never going to watch it.”

It was the mid-1980s. I was a high school student, working

for the former Dark Shadows star

nights and weekends on a series of one-man shows that had originated at fan

conventions and went on to tour nationally. No money was exchanged for my

labors, but on occasion the 60-year-old actor would give me memorabilia.

Considering he was the closest thing I had to an idol, I found this far more

rewarding than getting paid.

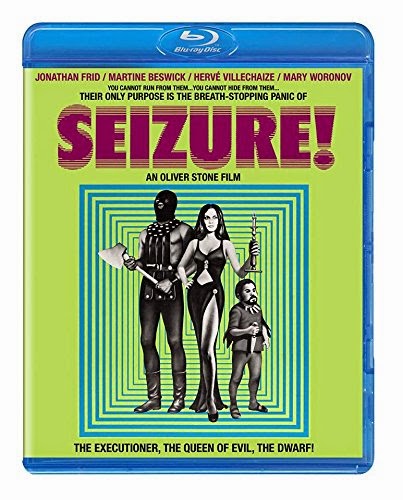

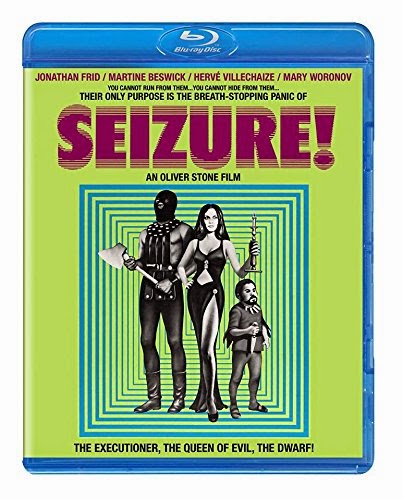

This particular piece of video remuneration was

SEIZURE, the

independently produced thriller Frid made in his native Canada in 1974. He had

done very little high-profile acting work in the three years since the

cancellation of the show that made him famous, but Frid still managed to earn

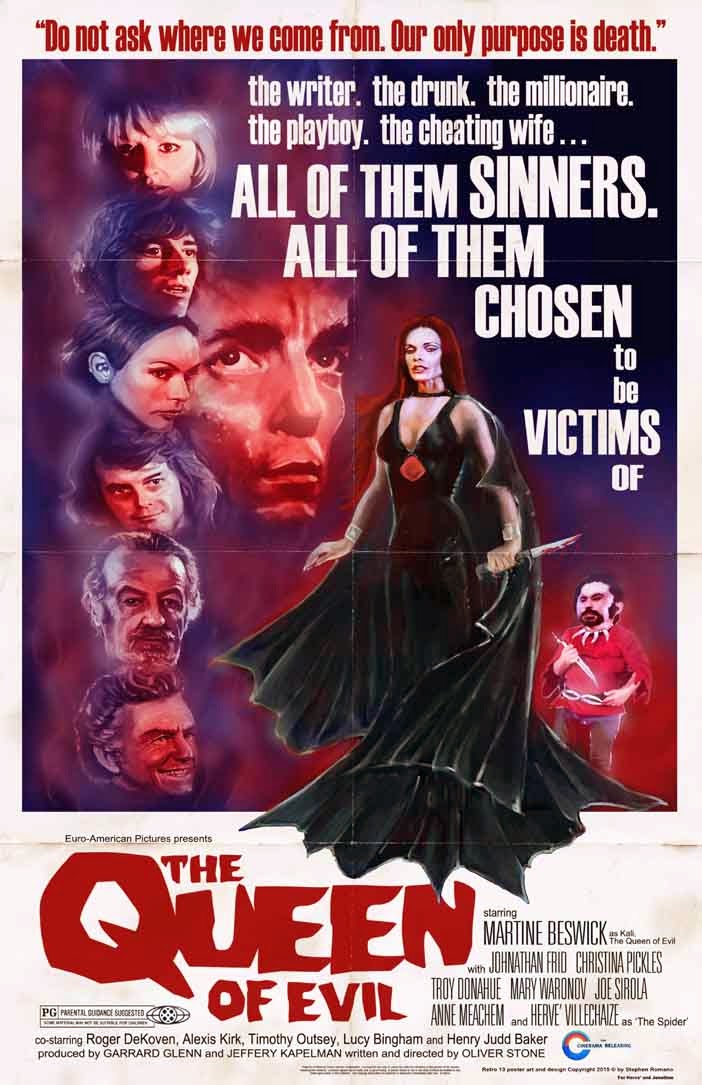

top billing. The cast was eclectic: Bond girl

Martine Beswick; former teen idol

Troy Donahue; soon-to-be

St. Elsewhere

nurse

Christina Pickles; one-time Warhol superstar

Mary Woronov; and future

Fantasy Island plane spotter

Hervé Villechaize.

But I didn’t care about the rest of the actors; my interest

was in the lead - because, at that moment in history, no

Jonathan Frid

performance was available on home video. The idea that 1,225 episodes of

Dark Shadows would someday be sold on

VHS (and again, on DVD) was the stuff of pipe dreams. You couldn’t even get

HOUSE OF DARK SHADOWS, the 1970 feature film based on the show, on tape back

then. I was forced to watch an off-air recording I made when the film aired -

in heavily edited form - on local TV.

And watch I did, so often that the oxide had begun to flake off.

There was a Jonathan Frid drought in those days, and the man himself had just led me to an

oasis. Not only was a Frid film on video for the first time, it was a movie I

had never seen. SEIZURE was legendary

among Dark Shadows fans. Although

only a decade old, it was considered a “lost” film, often mentioned in

fanzines, but rarely seen, due to some rumored shadiness by its producers.

“Manage your expectations,” Jonathan warned me, perhaps

sensing my enthusiasm. “It’s not very good.”

“You never think anything you’re in is good,” was my typically

smart-assed retort.

This was true. Like most demanding artists, Frid was harder

on no one more than himself. And Dark

Shadows, with its frequent flubs and technical limitations, was an exercise

in humility for its perfectionistic star.

Jonathan laughed. “We’ll see how you feel after you watch

it.”

I completed my tasks, left the apartment in Gramercy Park

and sprinted up to Penn Station for the Long Island Railroad commuter train.

Even though Frid’s building was only a few blocks from the subway, I almost

always walked there and back from 34th Street. My parents had only

just begun to allow me to travel into the city unaccompanied, and public

transportation was still “an uncertain and frightening journey.” I didn’t mind.

Walking made me feel like a real New Yorker.

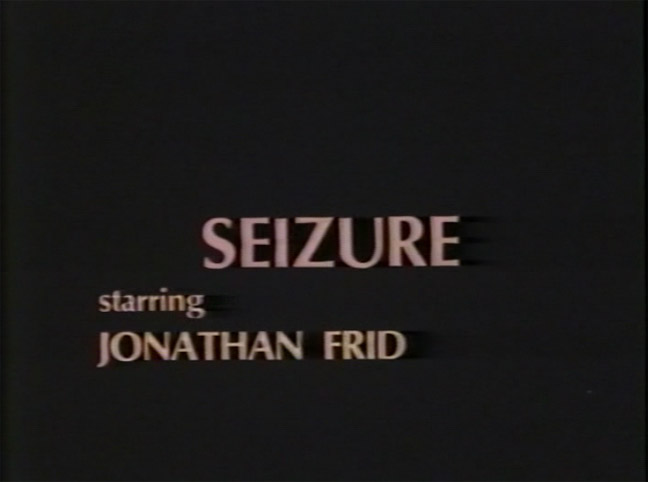

When I got home, I popped open the clamshell case and slid the

tape in my VCR. An ominous underscore rumbled out of the speakers of my new 19”

stereo TV, followed by what sounded

like the crash of a gong. “SEIZURE” the white-on-black title read, in all caps,

“Starring JONATHAN FRID.” This was so exciting, like unearthing a lost

Shakespeare play, or a previously undiscovered chapter of the Bible - The Book of Jonathan.

As the gong rang out, a folksy guitar kicked in, augmented

by a clarinet and electric piano. The score (by Canadian jazz recording artist

Lee Gagnon) was not what I expected from a “thriller,” but I’d watched enough

‘70s horror movies on late night TV to expect weirdness. The black screen

slowly dissolved to a pastoral lakeside tableau as the opening titles

continued, leading to a final credit that means more now than it did then.

Yes, SEIZURE was

Oliver Stone’s directorial debut, though he

has since creatively disowned it. He also wrote the film, with Edward Mann (a

syndicated cartoonist) and co-edited it. And his wife was the art director.

(They divorced not long after and, according

to Frid, bickered frequently during production.)

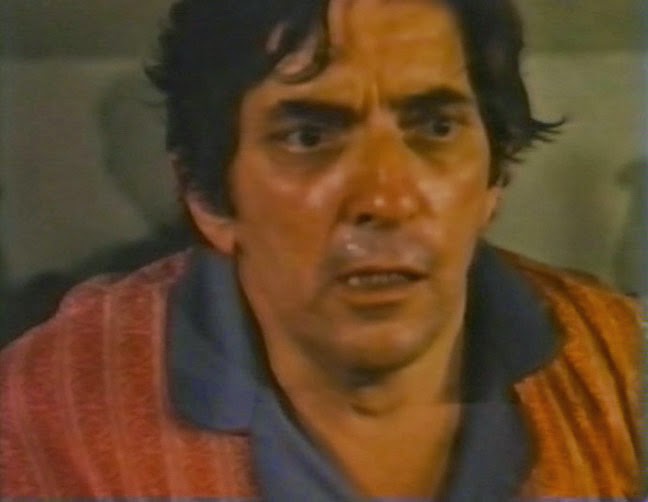

The film opens in a small, Colonial-style bedroom in a house

by a lake. Frid is asleep, in very un-vampiric striped pajamas. A towheaded

little boy rouses him, and he awakens with a scream, sweaty and startled.

“Mommy told me to come wake you up,” the boy apologizes.

“The guests are coming today.”

Cut to the bathroom. Frid’s character is shaving, in PJs and

tousled hair (no “Barnabas Bangs” in sight). His wife (Christina Pickles) walks

in and looks at him with concern.

“I had the dream again,” he says mournfully. “Same one. Same

way.”

Three minutes in and so far, so good! As a

Dark Shadows fan, the reference to dreams

excited me, because they play a huge part in the show’s mythology. Series

creator

Dan Curtis supposedly conceived the original storyline in a dream

(complete with camera angles for the opening scenes), and a lengthy storyline

from 1968 involved characters (including Barnabas) plagued by recurring

nightmares that lead to real-life terrors.

“Is it possible?” I wondered. “Could this be a sort-of

unofficial Dark Shadows sequel?”

Frid plays horror novelist Edmund Blackstone, husband of

Nicole and father to Jason, (

Timothy Ousey), an adorable 10-year-old who bears

a striking resemblance to

Dark Shadows’ mischievous

moppet

David Henesy. The Blackstones have invited five friends for the weekend:

Charlie Hughes (

Joseph Sirola) a boorish entrepreneur; Mikki Hughes (Woronov),

his much-younger wife; Serge Kahn (

Roger De Koven), an elderly Russian

businessman; his death-obsessed wife Eunice (

Anne Meacham); troublemaker Mark

Frost (Donahue, still shirtless at age 38); and Nicole’s brother Gerald (

Richard Cox), who is inexplicably British.

Stone efficiently introduces the characters, and establishes

that there has been an escape from a local psychiatric facility. When

unexplainable things begin to happen at the house, we are encouraged to wonder

if they are real, or a fantasy concocted in the creatively curdled,

misanthropic mind of the author.

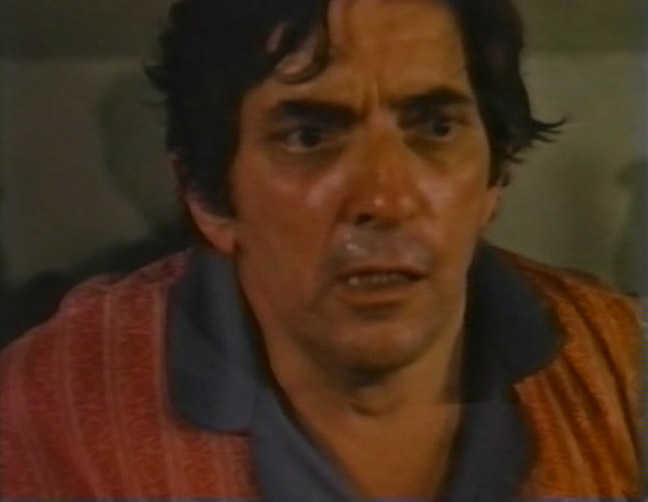

Frid always deftly negotiated the fence between good and

evil on Dark Shadows, and here again

he makes the most of Blackstone’s duality. He is ostensibly the hero, but his

behavior belies that when an odd trio of human monsters descends upon the quiet

compound.

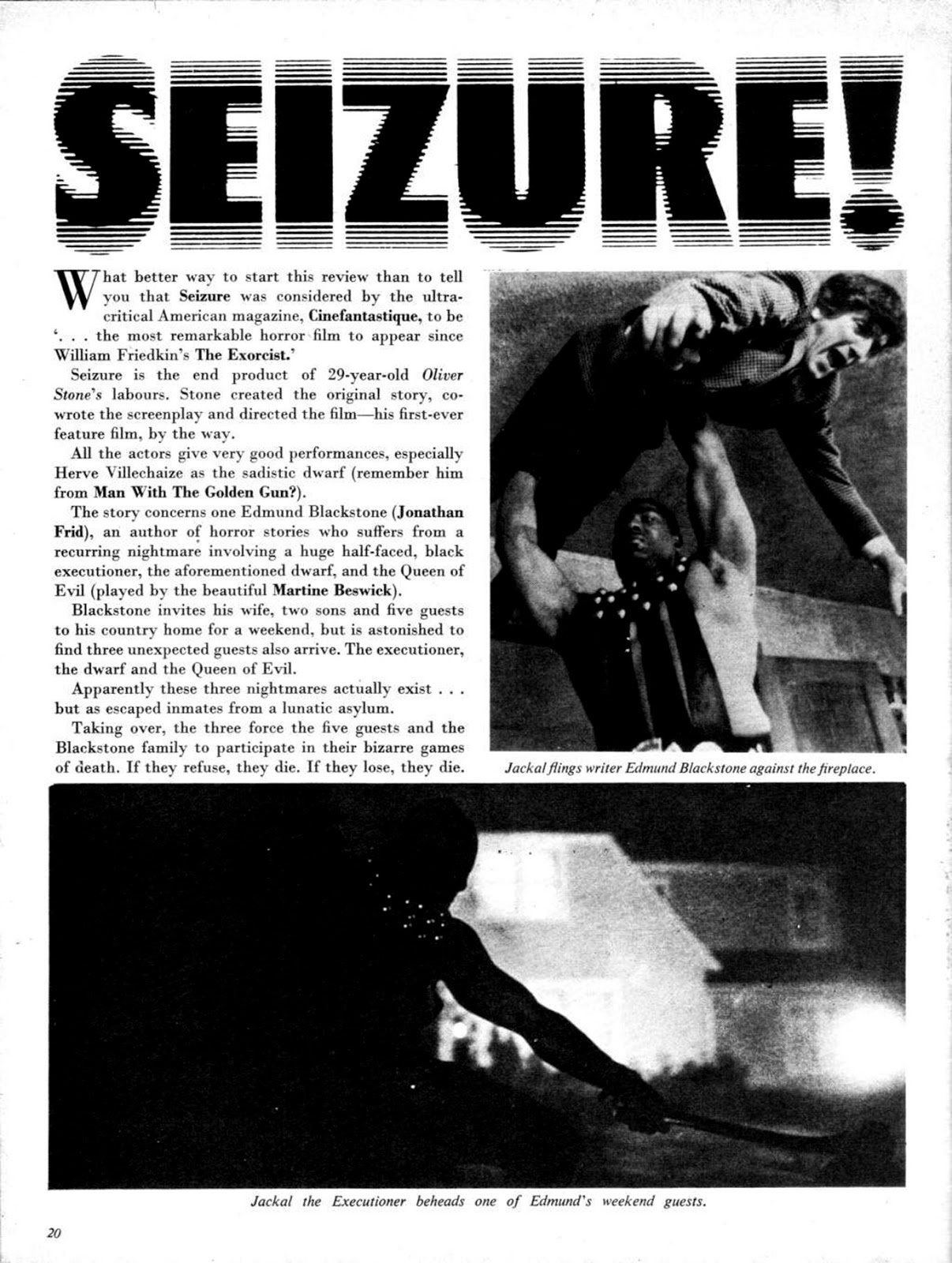

And odd they are. Beswick plays the sexy and sadistic “Queen

of Evil” (the film’s original title), said to be a manifestation of Kali, the

“dark mother” deity of the Hindu faith. Dracula-like, she twirls a black cape and

spouts stoner-Goth nonsense like, “Don’t ask us who we are, or where we come

from. We are without beginning or end.” Kali apparently enjoyed child

sacrifices back in the day, and the Queen spends much of the film seeking out

Edmund’s son in hopes of roasting him in the fireplace in her own honor.

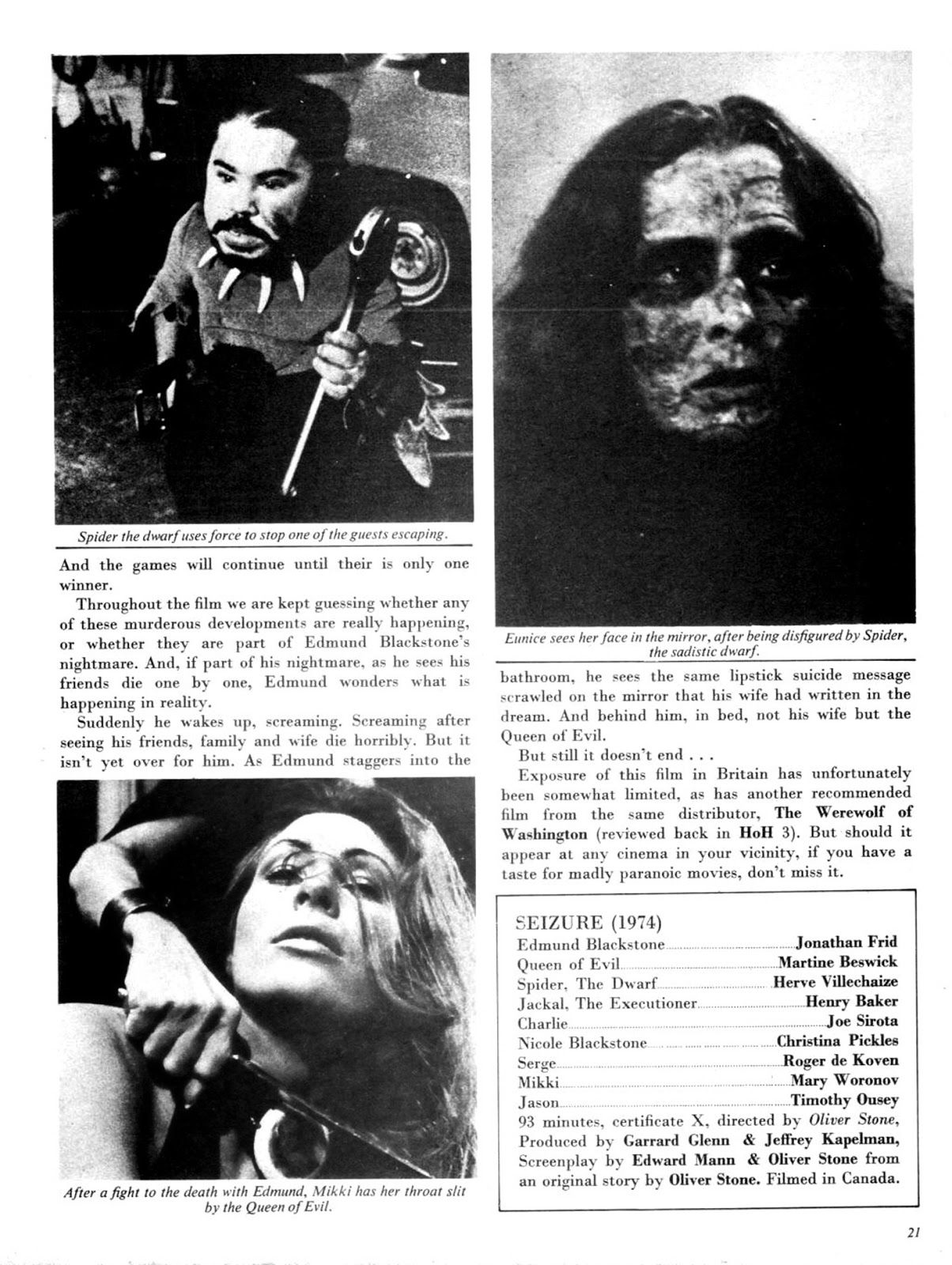

Villechaize is Spider, a bearded, knife-wielding dwarf (the

script’s description, not mine) preening about in red motley and a stylish bone

necklace. According to Serge (who’s primary narrative responsibility is

reciting long, expository speeches), Spider is the embodiment of Louis the

Cruel, a malevolent French prince from nearly a century ago.

“I am old

and I am ugly. But remember, my race was born inside your belly,” Herve

enigmatically proclaims, in an accent that is much harder to discern without

Mr. Rourke around to translate.

Villechaize

was also the on-set photographer, which may explain why all the stills are shot

from a low angle.

|

| See what I

mean? |

The last of

the baddies is The Jackal (Henry Judd Baker), a torturer “imported” from West

Africa to be a Russian executioner (again, according to Serge, who must have

read an earlier draft of the script). He’s also gigantic and mute, which means

there are no hilarious lines of his to quote. Coincidentally(?), Baker also

played the mute bodyguard Istvan on four episodes of Dark Shadows in 1969.

The Queen

and her henchman pit the vacationing friends against each other in a series of Survivor-esque physical challenges and

the cast members begin to slowly eliminate each other, one by one. Along the

way, we get to see Jonathan Frid making out with (and getting felt up by) Martine

Beswick, knife fighting a half-naked Mary Woronov and engaging in a brief love

scene with Christina Pickles.

While

SEIZURE shares some storyline similarities with

Dark Shadows - the dream motif, overlapping realities with

uncertain boundaries, a female villain calling the shots - it’s completely different

in tone and content, and far less charming. But the modern-day setting, and the

mortal nature of the lead character allow glimpses of a Jonathan Frid I never

saw on

the soap. In real life, Frid

was a complex man, sometimes short-tempered and mercurial of mood. There are

moments in this film when the character of Edmund Blackstone reminds me of the

guy I knew in a way that Barnabas Collins

never

did. That may be in part what appealed to Frid about this project - the

opportunity to play a flawed protagonist whose evil grew from human cowardice,

not from the supernatural.

Looking objectively

at SEIZURE

today, I agree with Jonathan’s assessment.

It’s not very good. But back then, I thought it was the greatest thing ever. I

loved seeing him in horn-rimmed glasses, wearing clothing he still owned a

decade later. I caught traces of his Canadian accent creeping into his dialogue

and noticed that his character used an expletive Jonathan himself was

particularly fond of. This was the closest to “the real Jonathan Frid” I had

ever seen on screen, and was ever likely to see, considering that he had essentially

retired from film acting after making two movies that he hated. As a kid who

looked at Frid as a unique combination of father figure, mentor and friend,

this was just about the best gift I could get.

I played

that tape at least once a week for months,

to the point where I had memorized every one of his lines. I never admitted

that to him, of course. I liked the fact that, though I was young, Jonathan

respected me and treated me like more than just a fan - even though that’s what

I was, and remain.

“So what’s

your review?” he asked, the next time I came to work.

“It was

okay,” I said, still playing it cool.

Jonathan and

I talked a bit more about the movie that day, and how, due to budget

limitations, the cast and crew lived in the house in which they filmed. He made

it sound like a glorified student film, particularly when he mentioned that the

“young director” was a recent graduate of New York University.

“(

Dark Shadows producer)

Bob Costello is a

professor there,” he said to me. “Maybe you should look into that school.”

And that’s

what I did. In the fall of 1986, I entered the Undergraduate Film and TV

program at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Frid was the subject of my sophomore

documentary, and my senior thesis film was based on a short story he performed

in his one-man shows. It was a piece I had found for him, during one of the

many Saturdays I had spent trolling my local library for material. Jonathan

came to the premiere of my film in 1991 and offered a review even more concise

than the one I had given him, years before.

“Perfect,”

he said.

I bought a bootleg

of SEIZURE recently (it’s never been legitimately released), put it in my DVD

player, and was immediately transported back to that first viewing more than a

quarter of a century ago. It’s amazing how much of the film I remembered, how

many of the lines I could still recite along with him. One of them had particular

resonance, considering recent events:

“An artist

is without end,” Frid says, in his final scene. “He can never die.”

Will McKinley is a New York City-based writer, producer and classic

film obsessive. He’s been a guest on Turner Classic Movies, Sirius

Satellite Radio and the TCM podcast. Will has written for PBS and his

byline has appeared more than 100 times in the pages of NYC alt weeklies

like The Villager. He watched his first episode of "Dark Shadows" on

April 12, 1982 and hasn't been the same since.