By ANSEL FARAJ

This is not a dream ... not a dream ...

We are using this book as a receiver. We are unable to transmit through conscious neural interference. You are receiving this broadcast as an essay.

We are transmitting from the year 2-0-1-4.

You are receiving this essay in order to alter your plans for the evening and to watch John Carpenter’s most underrated movie, PRINCE OF DARKNESS.

Our technology has increased, our cinematic resources have increased and we are capable of making flashier, crazier films; but we are incapable of making horror films that understand that it is the idea of the unknown which is truly frightening.

John Carpenter has made some fantastic works of cinema — HALLOWEEN, THE FOG, ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK, ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 and of course THE THING; but I feel PRINCE OF DARKNESS always seems to get short shrifted, and I don’t know why.

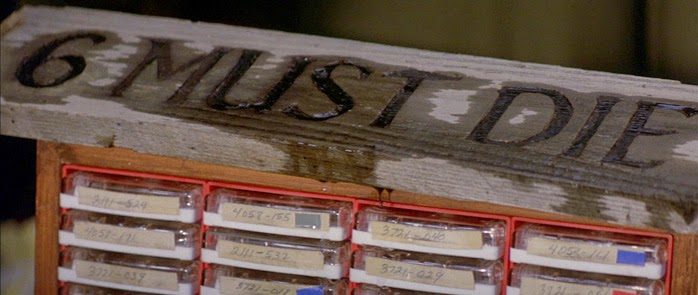

There’s a canister containing a swirling green liquid that is hidden in a set of catacombs beneath an run-down church in downtown Los Angeles. This liquid is actually a life-form that can perform telekinetic activity, mind control, body invasion. It’s even affecting the world on a cosmic scale — the sun and moon are aligning, the earth is changing, and this liquid life form is gaining power. It’s the “son” of a banished evil, a force of darkness — the antichrist, the “Prince of Darkness.” The Catholic Church has kept this a secret, forming a society named ‘the Brotherhood of Sleep’ to watch over it. Science must prove its existence and find a way to stop it. And whoever comes in close proximity to it, has the same dream ... a warning sent through time.

I first saw this film on Halloween night 2008, I was 16, and I found myself glued to my television, filled with the strangest sense of uneasiness. So uneasy, in fact, I had to take the DVD out mid way through and switch it for BLADE. I’m not sure if the uneasiness had to do with the fact that I was up really late at night watching PRINCE OF DARKNESS on Halloween night, or if it was because I was up really late at night watching PRINCE OF DARKNESS before I had to get up early the next day to take the SAT. But it must have been the former, because the next day, post-SAT, I resumed PRINCE OF DARKNESS and felt all chilly inside once more.

Here’s why I love it:

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again — if you can deliver effective atmosphere and a realized “world” in a film, then you have accomplished no small feat. And PRINCE OF DARKNESS has some of the best atmosphere I’ve seen in any movie. The story and mystery slowly get peeled away as the film progresses, fueled by a score by Carpenter and Alan Howarth that is icing on the cake. It’s a slow burn movie, filled with existential and scientific questions about life, our universe, God and the Devil, drenched in a Lovecraftian ooze. And when shit does get crazy, it’s pretty unnerving. There are multiple moments in the film where one can feel a chill down one’s spine. For me, it’s when Donald Pleasance’s unnamed priest loses his faith in the middle of performing the last rites on an unfortunate victim. The equal mixture of horror and “why bother?” that crosses his face stuck with me the first time I saw it.

The group of homeless people — some people have called them zombies, but I disagree — come across more as cult members, being controlled psychically by the Prince of Darkness locked up in his canister. I love how they watch from the sidelines, staring quietly, waiting to carry out his bidding. It always felt very INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS to me, and was something I referenced in my film, DOCTOR MABUSE. They bow to unseen forces, are covered in bugs, and are led by a sneering Alice Cooper. Carpenter uses them to great effect as they trap the unsuspecting group of physicists in the run down downtown L.A. church, a ploy he uses in most of his films, such as THE FOG and THE THING. These are films about people trapped together, fighting a force they have no control over, which something that is frightening in itself. We have no control over anything in our lives — we just tell ourselves we do. Carpenter’s work reminds us of that awful truth.

|

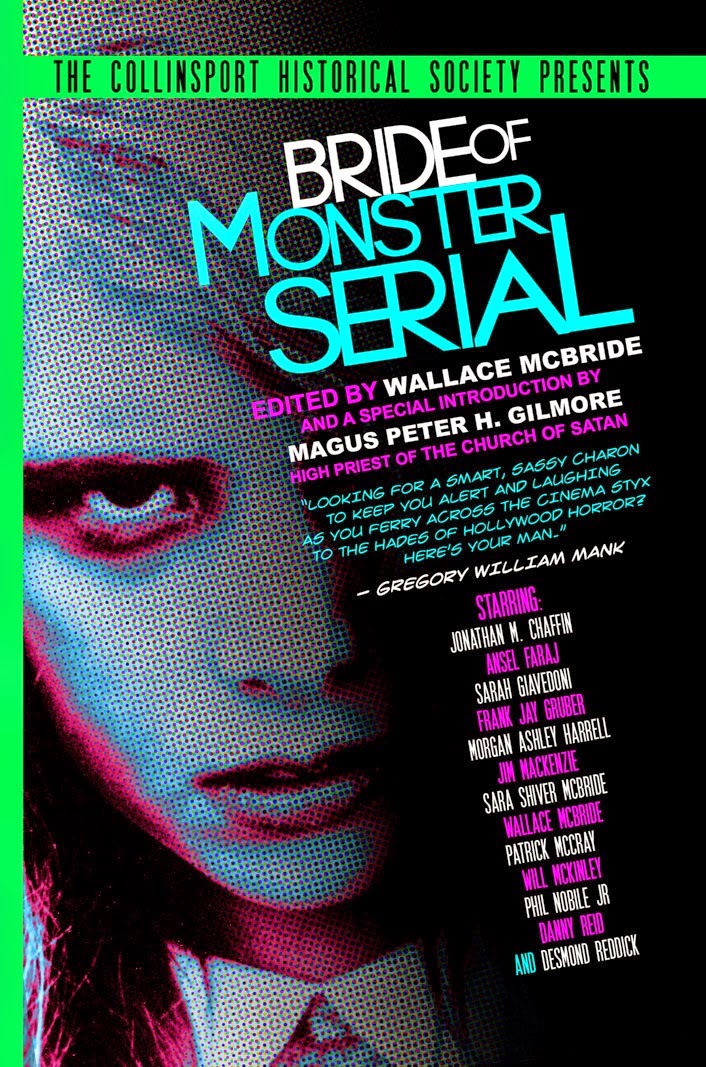

| This column is among those featured in BRIDE OF MONSTER SERIAL, a collection of horror essays written by contributors to THE COLLINSPORT HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Buy it today on Amazon! |

Worse, how do we react when something beyond our normal perimeters of logic, common sense and human origin begins to control us? What if it always controlled us?

The crucified pigeon — it’s just a moment early in the film, but it’s the perfect prelude to what follows — is a symbol of how darkly surreal the film is about to get. Some moments feel like they’re out of a Dario Argento movie: There are scenes that would be at home in SUSPIRIA or PHENOMENA. And there are even moments where Carpenter seems to be channeling Jean Cocteau, specifically in his usage of mirrors as gateways to a dark dimension where the Devil, or more accurately, the Lovecraftian elder god we perceive as Old Scratch waits to be brought back through. There’s a great shot where a pair of fingers push through a compact mirror and come through on the other side, a dark watery abyss. It’s a moment that would not be out of place in a PHANTASM movie, and here Carpenter uses all of these moments to build up his atmosphere of dread — at what, or who, is waiting for us on the other side.

I’ve got a message for you, and you aren’t going to like it.

PRINCE OF DARKNESS knows what lurks in the unknown. It is evil. It is real. It awakened back in 1987, and got poor reviews. But the Devil always gets his due, and now’s the perfect time to go back and re-appreciate this film. Grab Scream Factory’s fantastic Blu-ray, turn the lights off, and watch. Seeing is believing.

Ansel Faraj is an award-winning independent American film director, screenwriter, and producer. He recently wrapped production on his latest film, DOCTOR MABUSE: ETIOPOMAR.