Taped on this date in 1970: Episode 1169

By PATRICK McCRAY

When Angelique declares her love for Barnabas and lifts his curse, Judah realizes that the former vampire’s human side is a dangerous place to be. Judah Zachery: James Storm. (Repeat; 30 min.)

Barnabas interrupts Gerard’s daytime quest for his coffin by appearing quite human, having been made so by a contrite Angelique. Meanwhile, as Angelique reveals her history as Miranda Duval, Gabriel is haunted by the ghost of his murdered father, and attempts to kill Gerard.

Everything has to grow up.

It would have been just as school was letting out for the holidays. Kids were three years older than they were when they spent their first (significant) DS Christmas break in 1795. I know that the show wasn’t expressly aimed at them, but, well, it was, anyway. Sam Hall was the father of a twelve year-old boy, and thus, was not only aware of their evolving sensibilities, but of their schedules, as well. School was letting out. Although kids were hme all the time, they also had more things bidding for that time. The show would kick it up accordingly. 1795 existed to show the knotty nature of pursuing passion’s industry. It’s appropriately two-dimensional for kids first learning about the basics of new love, infidelity, and the occult. Three years later, the lessons of ep. 1169 are far more nuanced, dealing with last loves, true loves, and a love so enduring that it grows past romance and into actual respect, affection, and admiration.

It’s my understanding that the ratings were not as problematic at this time as history later implied. Still, Dan was increasingly restless, they had a star who was desperate to play anything other than the show’s sensation, and, not being a genre writer, Sam Hall himself was growing exhausted and bereft of fresh ideas. It’s a natural time to start asking where this is all going. Dark Shadows was not a sustainable organism because of its very strength… the wild ideas that sparked the story and the vast number of episodes they had to enliven. While that may seem kind of sad, it makes it the Roy Batty of daytime TV, finding a life with shape and meaning because of its limited lifespan. Other soaps may have memorable storylines and characters, but are they a memorable story? It’s impossible. But as unwieldy as Dark Shadows seems to be, there is a story within it. Like the Garden of Earthly Delights, it may be a massively complicated and surreal mess, but there’s a frame, and if we step back far enough, it’s all there to be seen at once.1168 makes us acutely aware of that. As a piece of dramatic structure, it suffers from the endemic curse of its medium: the most vital moments are in the first act. Why? Today’s first act is actually the resolution of yesterday’s climax. So often with Dark Shadows, the episode begins with yesterday’s crescendo, but unlike the countless other entries in the saga, it does more than pad the running time until setting up the next episode’s big beginning. Hall is cleaning house, taking chances, unwrapping surprises, and, seemingly, hanging out with dear friends he knows are going away.

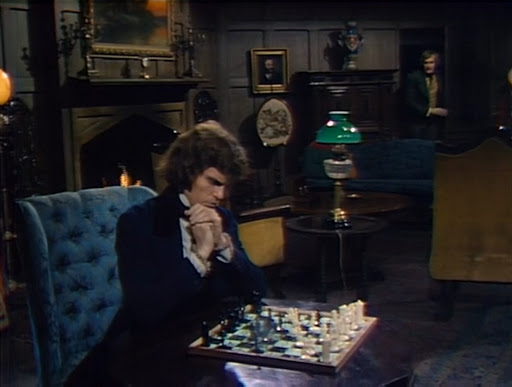

So, if they are going away, what can he do for them? How can he thank them? You know, “them” being not only the characters, but the actors who were his inevitable collaborators. Let’s start with James Storm, who has the opportunity to delve ever deeper into the character of Judah Zachery. Zachery, at this point, is so close to victory that he doesn’t seem to care. Storm has enjoyed one of the show’s rarest delights as he subverts one deceitful character for another entirely different deceitful character, but never really taking the spotlight as he should. He’s competing for airtime with the program's most saturated and robustly charismatic male ensembles. Given that, he’s practically Elvis, and the field of near-metadrama is his ‘68 Comeback Special. How many layers? We have Sam Hall writing for James Storm playing Judah Zachery possessing Ivan Miller pretending to be Gerard Stiles. That’s not confusing. It unrolls at a stately pace. Rather, it’s generous. Storm is so nimble and meticulous in his performance, you’d think it would turn clockwork. No. His singular magic is to fuse that almost pointilist precision of thought and language with the Halloween-night joy of simply performing. And he’s in marvelous company, because Christopher Pennock is allowed dazzling range here as a Gabriel pushed to the edge. Planning, calculating, and swearing vengeance, he’s a murderer trying to shift the blame onto Gerard. And from a certain point of view, he’s correct. But like a twisted riff on Hamlet, he’s tortured by the ghost of the father he murdered, and this spectral patriarch may not be omniscient. He’s still there to take it out only on Gabriel, and you would think that, in death, he would see the puppet strings of both Gerard and Judah, at the very least spreading the blame. But Daniel seems myopic to this, and the frenzy of ghostly guilt and greed seems to galvanize Gabriel (hang on, let me catch my breath) into taking his first actions to preserve the Collins legacy. In Dark Shadows, you don’t even bother to hope that your ancestors will go to a better place. You just double it on the pass line and pray they didn’t see what you did.

On the blueprints, the dullest and most thankless part on the show had to go to Grayson Hall, who’s not crazy, supernatural, newly human, possessed, nor haunted. Her edge comes from the fact that Sam had to sleep some time, and if he thought he was going to turn her into a wandering sounding board for exposition, he’d better sleep lightly. Having only guts, common sense, and enough experience to know that Blairs and Petofis come and Blairs and Petofis go, she’s one of us looking in. Judah doesn't stand a chance.

In her attempts to reason with Barnabas, we see each appreciating and suffering the lack of what defines the other. Julia is memory. Fact. Common sense. Barnabas is a creature high on the fumes of pure relief and affection. Is it possible that Angelique is staging all of this for a royal screw worthy of Wile E. Coyote? Yeah. But… you know… it’s also possible that she’s sincere. We have no evidence. So, yeah, she did this out some newfound goodness in her heart. It’s possible. What? Stop lookin’ at me like that. It is. And as it turns out, I’m right.

Lara Parker plays the dishwater dull role of Proving She’s Earnest and then Giving History Lessons. That kind of goody-goody nonsense and trip-down-memory-lane-ing is deadly for actors. However, these are also profound turning points for the character. Someone who’s lived only lies -- down to her very name -- for centuries is changing the dance. That’s a powerful lesson, and Parker plays it with a fierceness that communicates the absolute necessity of compassion and honesty. She’s tried everything else. If 1840 is anything, it’s a woman’s attempt to protect the man she loves from the machinations of a deranged ex-boyfriend. From the implications she drops about Judah, it’s clear he was a love of her past. How different he was from Barnabas, and perhaps that’s the point.

And this positions our craggy, handwringing hero to have moments in the sun at last… again. We see him through the eyes of Julia and Angelique as everyone tries to reconcile that, yes, we have the capacity for change. Even the worst of us. Jonathan Frid, a man who, three years prior, was damnably uneasy playing youthful innocence, now portrays the same man with ease. It’s an innocence that’s organic. It comes from knowing how complicated humans will make the world, and what a relief it is when they drop the act. Innocence like Barnabas’ doesn’t come from a lack of experience. It comes from seeing how little can actually come from it. And relishing pulling the rug from beneath Gerard? As well as showing off his Mrs. Peel? It’s been a long time coming.

This is all in 24 minutes, and that just begins the goodbye.

This episode was broadcast Dec. 17, 1970.