By FRANK JAY GRUBER

We never again get scared the way we do at age eight. At eight we’re old enough to know the world is a bit more complex than moral fables would have us believe, and there’s a growing suspicion in the back of our brains that maybe Mommy and Daddy don’t know everything. Maybe nobody does. It’s a few years more before we learn enough for this to be a certainty.

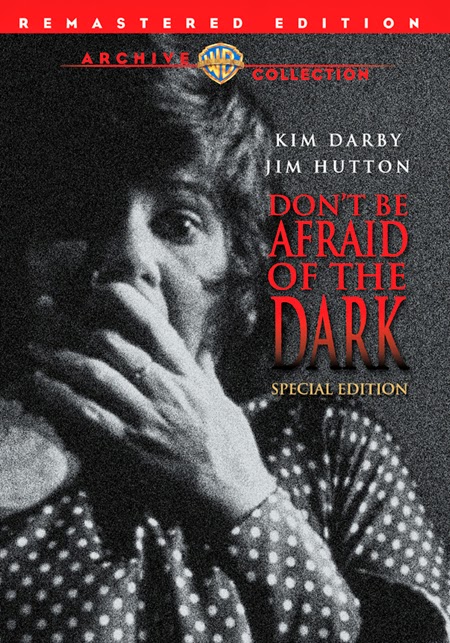

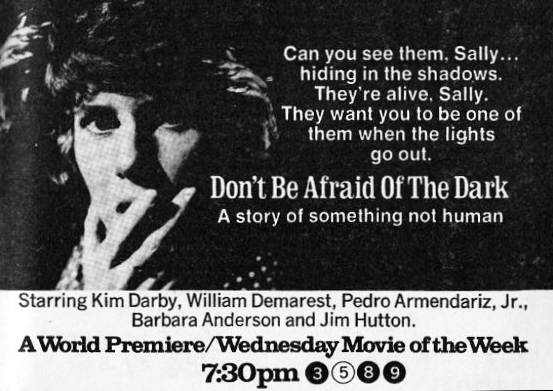

October, 1973: Eight year-old me sits on the sofa in our suburban apartment’s living room, probably with mouth hanging open eagerly, definitely with legs tucked up under me—Who knows what might be scurrying along the floor, grasping at my legs with feverish strokes of tiny claws?

All week long I’ve seen commercials for a TV movie that my mother thought far too scary for her innocent son. I would not be allowed to watch it. Yet there she is, asleep in the chair, her crocheted afghan incomplete on her lap. Dad sits at the dining table on the other side of the room, working on a jigsaw puzzle and oblivious to the third-grader going insane with worry and fear about eight feet behind him.

First comes the ever-pompous ABC Movie of the Week tune—viewers know they’re going to see something intended to be important and great, even if it turns out to be total drek like The Mod Squad reunion movie (Solid, Link? I don’t think so).

A succession of images follow: The moon breaking through clouds, a black cat, a vaguely Gothic house, a gnarled tree, autumn leaves blowing—and this is all within the first minute. It’s a Halloween fantasia. Somewhere on the other side of the country Ray Bradbury is probably heaving with excitement.

Suddenly little over-processed voices start asking questions like “Will she come? Do you think she’ll come?” From the weird intonations and repetitions of parts of phrases you know two things: These are not normal people and there are several of them.

I wouldn’t have registered at the time that the opening credits listed John Newland as director. I didn’t stay up late enough to catch One Step Beyond on late night repeats. I’m glad I didn’t know Newland’s show dealt with creepy and inexplicable events and horrors that were reputed to be true. Yep. Glad I didn’t know.

What follows is the first daylight scene. Like many horror pics, the film has an alternating structure between the normality of daylight scenes and the encroaching horror of the interiors and night.

The house looks different by daylight. It’s all pastel hues and soft colors. There are flowering trees outside. I often think Frankenstein’s Monster must have looked pastel green and sweet when the little girl met him for that flower throwing game that went bad. I’d love to have seen Karloff painted by Thomas Kinkade. All is peaceful and well this first morning.

Oddly, even the humans are initially heard in voiceovers:

“Alex, are you sure you don’t mind?” A woman’s voice.

“About moving in here?” A man’s.

We then meet Sally Farnham, an actress I instantly recognize as Miri from the Star Trek episode of the same name. You know, the one where the adults unleash some biological infestation upon the world, get a horrible skin disease, die in frothing madness, and all the children are left horribly alone. That one.

I identify with Sally immediately. Not only is she an adorable suburban housewife, but actress Kim Darby is really short and looks about fourteen.

Not only that, but the handyman she hired to fix up the place is Uncle Charley from My Three Sons. If he protected Chip and Ernie for years, what could possibly go wrong? Just as all the Halloween imagery beginning the film set a dark mood, the bright pastel morning and bringing in trusty Uncle Charley sends a different signal to viewers of all ages. How much does the terror increase later when even he can’t stop it? Sadly, William Demarest, clearly hired for his gravelly voice and ability to look worried, is to be no protection at all.

In a conversation with her interior decorator it comes out that Sally was left this house by her grandmother. She pulls him downstairs, fabric samples and all, to look at the basement. The door was locked, but they found the key among Grandma’s unmentionables. No, they don’t mention them. Stop thinking of Grandma that way. It was in an envelope in her desk.

Sally says she doesn’t think the basement room has been used since Grandfather died.

“How did he die?” I ask nobody. My father looks up, grunts, and goes back to his puzzle.

Not only are all the window shutters nailed tight, so as not to let in the light, but somebody bricked up the basement fireplace. The bricks are four deep and reinforced with iron bars. Grandpa clearly hated s’mores.

Turns out Uncle Charley—I mean handyman Mr. Harris —did this on Grandma’s instructions twenty years ago after Grandpa ... we won’t say.

“WHAT ABOUT GRANDPA?” I ask.

“We’re seeing him next month,” my mother mutters in her sleep.

“Some things are better left as they are,” Mr. Harris says, as if to answer me.

Okay, I think. My imagination has Grandpa sucked into the fireplace by the owners of the weird voices and dear old Grandma and worried looking Mr. Harris hushing it up.

“Morris?” Grandma would have said to the detective. “He went to visit his sister. I think she’s with a travelling circus. No idea where he is.” Mr. Harris would nod in agreement, covering for her the way he did so effectively for Chip and Ernie.

But now Grandma was dead and the chimney vocalists are hungry again. Here’s my question: Knowing about the evil in the basement hearth, why would handyman Harris let the nice young family move into the house in the first place? Why not burn it down? Why not sell it to that charming family from Amityville? Why not do something?

“Some things are better left as they are,” he says again. Oh yeah. He has a policy of non-interference. In a textbook example of TV land cross-pollination, apparently Uncle Charley follows Star Trek’s Prime Directive better than Captain Kirk does.

Mr. Harris tries arguing Sally out of using the dirty old basement for an office. Her husband gets home in time to agree. It’s Jim Hutton, father of Timothy Hutton, about two years away from starring in his fondly remembered role of Ellery Queen. He agrees. The basement room is cold and damp. They should leave it be.

Jim Hutton’s character is a practical man, a thirtyish lawyer—which is probably just as well since he may be brought up on charges for marrying a fourteen year-old girl at any moment. He also towers over his wife by what looks like a foot and a half. He is the adult figure, the voice of reason and sanity, and is convinced everything inexplicable is in her mind. He’s also work-obsessed and driving hard for a partnership—which means he’ll be away much of the time, leaving Sally and her sotto voce midget friends to their devices.

Hutton’s Alex tells her to abandon her plan to open the fireplace. “See things my way?”

“I guess I’ll have to,” she responds. She should, after all, be a submissive housewife. Here are two men telling her to be sensible.

Sally, in a stubborn burst of decisive action—the results of which set women’s lib back about forty years—decides to not only defy the menfolk and use the basement as an office, but also unscrews the fireplace’s ash door and leaves it open. That’ll show them. “If only she had listened!” screenwriter Nigel McKeand seems to be saying. McKeand was later best known as a scribe for the Kristy McNichol series Family.

“Free! Free! She set us free!” cry the little voices. Is that a green glow?

Fade to black.

Commercial over, we pull back from a close up of the basement shutters bathed in an unearthly emerald glow for no particular reason. Not only no particular reason, but no explicable one, since this is the only window of the house shining at all. We expect a man with a goofy mustache to pop open the shutters and say, “Why didn’t you ring the bell? No, you can’t see the wizard!”

What follows is a truly disturbing sequence where the unseen critters—now free to crawl out the ash grate door—escape the basement by pushing the key from the other side, forcing it to fall on a piece of carpentry plans, and pulling it under the door—a crack illuminated by that same disturbing green light. Not only do they enjoy a good babble, but they’re deviously clever and apparently have access to old St. Patrick’s Day flashlights. This viridescent light and a scuttling sound are used to indicate their movement around the house.

The rest of the film is a journey into psychological terror that stands head and shoulders above any of my other childhood memories. Average rooms are turned into terror zones—and Sally doesn’t even have to get miniaturized like the guy in The Incredible Shrinking Man.

They first venture behind a trash can in the kitchen. We can see the hairy shadow of a tiny arm and a claw. Upstairs, as Sally sleeps, one is on her nightstand mere inches from her head. They call her name. Do they mean her harm? They do smash her glass ashtray, so apparently they at least want her lungs healthy.

Another pastel morning Sally is prowling an outdoor shopping mall with her friend Joan, played by Ironside’s Barbara Anderson. The two women have been friends for years. After all, they both had crushes on Captain Kirk during Star Trek’s first season. At this point Sally thinks the place may be infested with mice. In yet another knock at the changing times, Nigel McKeand’s script has Joan reply, “I don’t care what women’s lib tells me. The very mention of a mouse drives me crazy.”

Our first full glimpse of the creatures comes as Sally is throwing a catered housewarming party. All of Alex’s co-workers are present. At a moment that you can imagine the screenwriter himself giggling over, Sally gets something to drink and spots one of the creatures staring at her out of a flower arrangement. That’s right: She gets a literal punch and a supernatural punch at the same time.

Something must be said about the gremlins themselves. They seem to be about a foot high, with claws, suits of fur and heads that look like dried out peach pits. One of them is played by Felix Silla, Cousin Itt of The Addams Family and Twiki the robot of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. I hadn’t realized he was in this movie, so when I met him years ago I never knew to throttle him for scaring the heck out of me when I was eight.

Uncle Charley—Mr. Harris—revisits the house to pick up his tools. Earlier he tried resealing the ash door and was fired when the couple found it open again. The husband thought he was a practical joker. He tries to warn Alex, but only in the most general terms and without revealing any details. Even that was too much.

Uncle Charley gets his—ironically by three small fry—as they cut open his hand and chant “You told him! Why did you tell? You know what happens to people who tell!” He barely escapes with his life and is not seen again until the end of the film. Presumably he spent the time shivering under Fred MacMurray’s couch somewhere muttering “I’ll never moonlight again. Carpentry? Bah!”

The creatures also kill the decorator by this point, for reasons that remain unclear. He wasn’t planning on redecorating the basement. Perhaps they didn’t like that he was going to carpet the stairs in blue. It would clash with their evil green light. They do him in by that tried and true method of stringing a line across the top of the stairs. Down he goes, fabric swatches flying. A bizarre tug of war ensues, with Sally trying to snatch the cord away from the creatures.

“We want you! It’s your spirit we need! Become one of us! Live with us!” say the gremlins. Sally says nothing. In fact, her silent response to the creatures becomes unsettling in itself. Only in the final scenes of the film, when she is doped up, does she have an excuse for this strange silence. She only shrieks once in the film, when one of the critters snatches a napkin off her lap during the party scene. Other than that moment, she remains almost expressionless much of the time—as if she knows her inevitable fate.

After the decorator is killed and Sally is resting in her room comes the iconic shot of three gremlins hiding behind books in Sally’s bedroom bookcase. This is a strange perversion of something every reader who ever owned a cat has experienced. Sally refuses to take any sleeping pills, yet the box is open and two are missing—and there’s Sally’s coffee right next to the package.

At friend Joan’s insistence, husband Alex rushes off to see carpenter Harris to get the real backstory. The house was built circa 1880. The fireplace was bricked when Grandma and Grandpa moved in. One day he decided to unbrick it, worked in the basement for about a half hour, and started screeching. The basement had been trashed and Grandpa was gone into the fireplace. Why burly 1950s police officers with flashlights and long ropes never went down looking for him is never addressed. They could have brought in the guys from Them! They had spelunking experience and would have wiped out any giant ants they came across as a bonus.

The husband and Harris rush back to find Joan locked out of the house and the power cut. Apparently Grandpa, now presumably one of the gremlins, clued them in about how electric wiring works. Sally is in there with them alone, zoned out of her mind on the two missing sleeping pills. By the time they break in and get to the basement it’s too late.

|

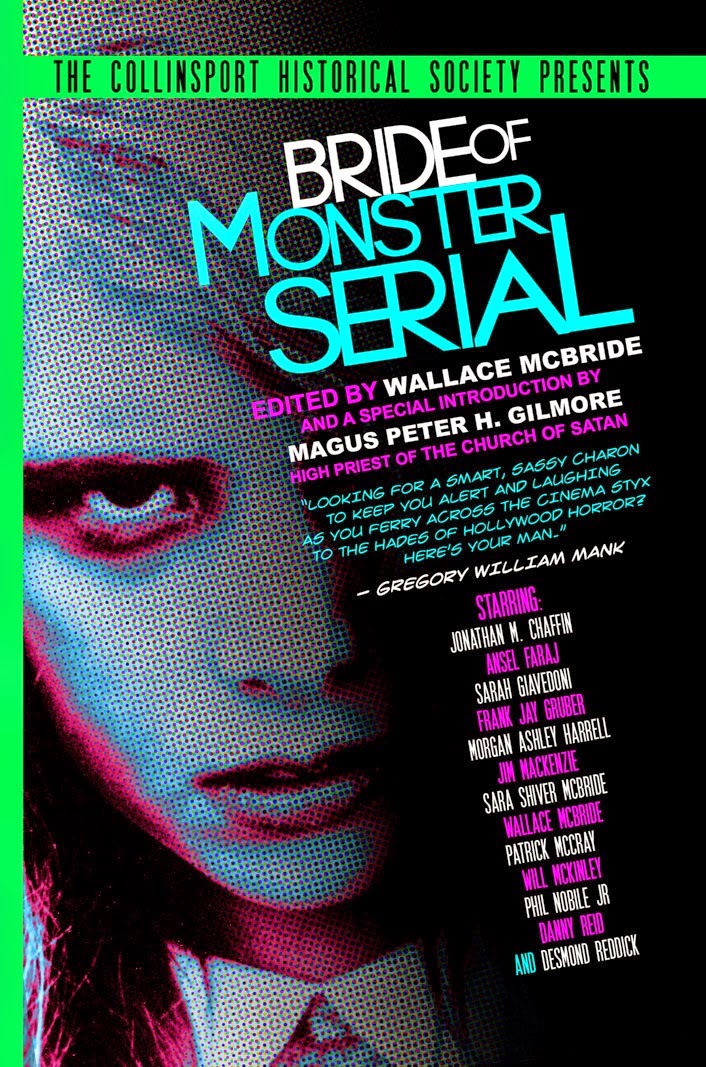

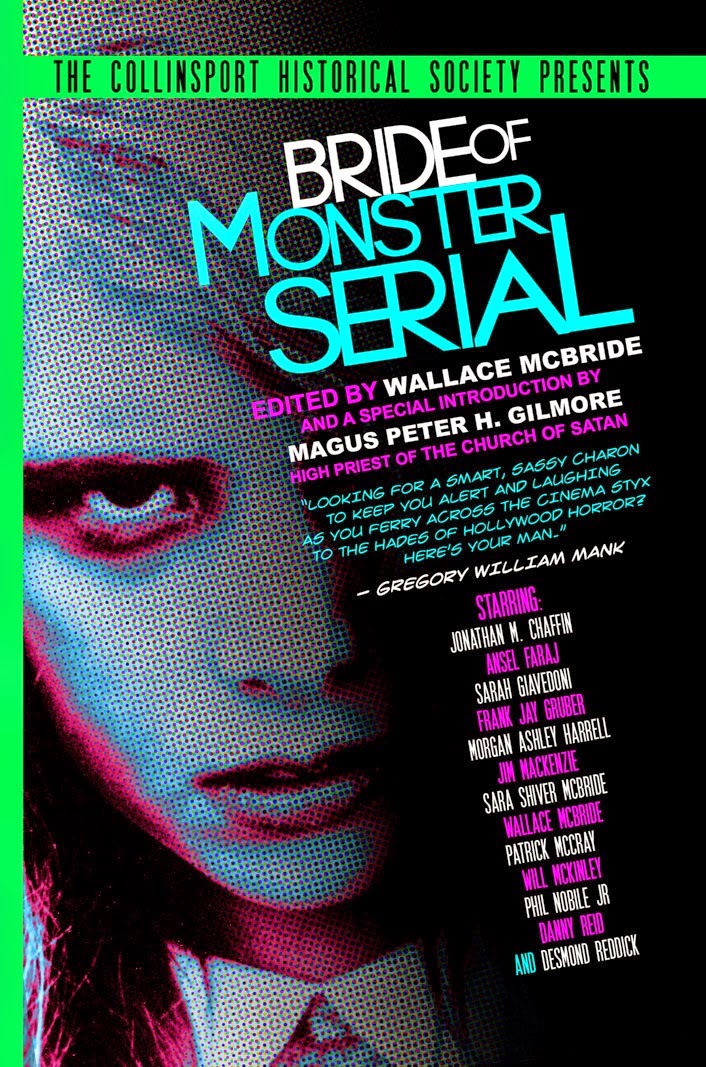

This column is among those featured in

BRIDE OF MONSTER SERIAL, a collection of

horror essays written by contributors to

THE COLLINSPORT HISTORICAL SOCIETY.

Buy it today on Amazon!

|

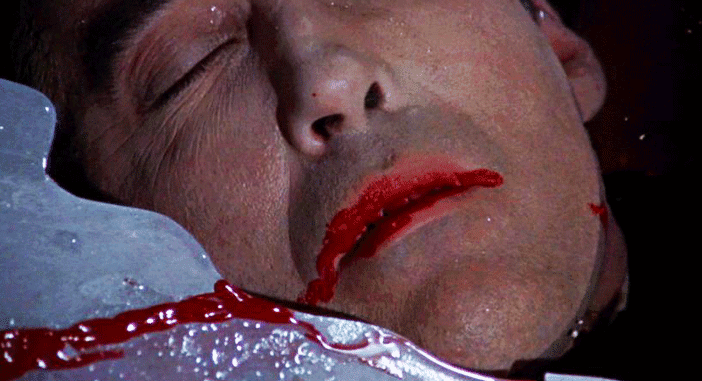

The movie’s finale is probably the most memorable cinematic scene of my childhood. Drowsy Sally’s legs are tied and the gremlins pull her slowly down the stairs towards the basement. Luckily, Joan’s husband George left his camera behind at the party the other night. Sally snatches it off a table as she’s dragged past. This moment, where she only has a little 1970s camera and a set of flashcubes to ward off the creatures by blinding their sensitive photophobic eyes, is stunning even by today’s standards. It will live forever in my memory.

As will the film’s dark ending.

The resolution, if you can call it that, is bizarre in itself. Sally is dragged through the ash gate and into the fireplace. Her husband, Harris and Joan are too late to save her.

Sally is not dead. Instead she apparently becomes the mistress of the creatures—kind of a short Snow White with some really ugly dwarves—and we hear her conversing with the gremlins in the basement. The creatures want people to come and “set us free in the world!” She consoles them by saying, “Of course they will come. We know they will.”

They laugh gleefully.

As the credits roll, I am no longer on the couch. I am behind my mother’s chair, visibly shaking. My parents died years later without ever knowing I’d watched that movie—only that I developed a permanent aversion to both sitting with my feet dangling on the floor and the color green.

DON’T BE AFRAID OF THE DARK would be all we talked about in our third grade classroom the next day.

But school was a long night away—and who knew what might be scurrying underneath the bed before then? I didn’t even have useless Uncle Charley.

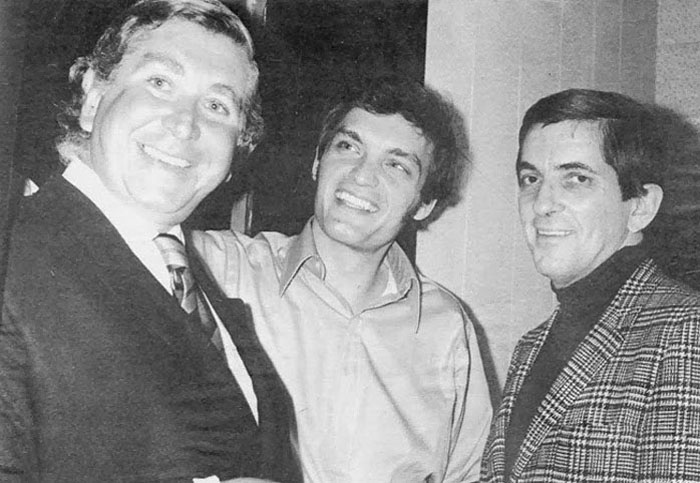

FRANK JAY GRUBER In addition to his freelance writing and editing gigs, Frank Jay Gruber teaches literature, composition and online course development at Bergen Community College in New Jersey. He sometimes covers New York and Philadelphia area events for TrekMovie.com, appears on convention panels and writes for genre websites like The Collinsport Historical Society. CNN interviewed him about Star Trek in his collectible-covered lair and consulted him about Dark Shadows after Jonathan Frid’s death in 2012. You can read his extremely infrequent musings at TheWearyProfessor.com and follow him on Twitter @FrankJayGruber.