Taped on this date in 1970: Episode 1165

By PATRICK McCRAY

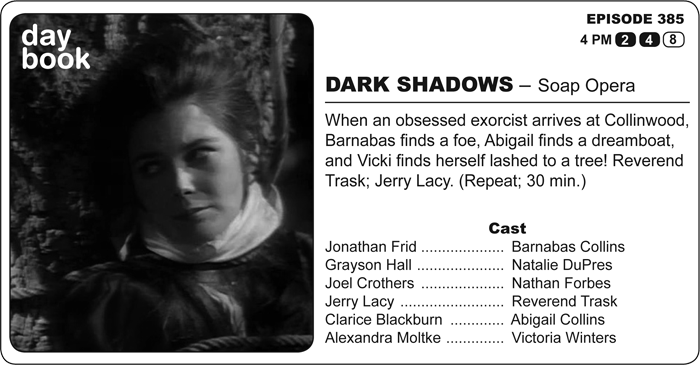

Tad finds out that justice can be a mother when Samantha performs her wifely duty of trying to get her husband beheaded. Tad: David Henesy. (Repeat; 30 min.)

Even though the county prosecutor quits his job over the inanity of Quentin’s trial, the figures of Official Justice insist it go forward anyway. When he’s replaced by someone played by Humbert Allen Astredo, Quentin knows it will not go well. Meanwhile, although Tad begs his mother to testify on Quentin’s behalf, she instead takes the stand against him. Quentin responds by sitting around and pretending not to notice how handsome everyone thinks he is.

It's David Henesy's last day on the program. It's a sad graduation. It's a quiet graduation. It's the kind of graduation that means a lot more to the adults than to the people actually going through it. Like all graduations, I guess. It's hard to tell whether or not they intended this to be his last appearance. He was at an awkward age for the program. You couldn't get away with any of the juvenile plots of him doing something out of naïveté. Yes, he could be turned into a delinquent, but that’s a move the show might not be ready for. Even in the world of David Cassidy and Bobby Sherman, he's not quite old enough to be an official teen idol without it feeling just a little bit creepy. All of this... packed into someone of middle teenage vintage who nevertheless has a voice deeper than Brock Peters.

His farewell to the program consists of one scene, and it shows the influence that Tad should have on his world. With his father accused of witchcraft, Ted expects his mother to testify on her husband's behalf. Virginia Vestoff does a wonderful job trying to bend and weave around Tad's expectation, preparing herself to survive whatever kind of confrontation will follow whatever stunt she pulls on the stand.

Although no relationship in life improves after the first date, it is the last conversation that permanently frames us with each other. Given that these characters, via specific actors, turn up over and over and over again in era after era, it's pointless (in some regards) to see them as anything other than one figure with many masks. All of the David Hennessy characters might as well be just one David Hennessy character. And if we look at it that way, what do we learn from this?

Well, for one thing, this character was much better at talking people into things back when he decided the rules were meant to be broken. Like Britannicus in I Claudius, I feel like he's become obsessed with "putting on his manly gown," maybe because he doesn't wanna wind up like Laszlo. Either way, he may be becoming all leading man (at least on the chalkboard in his dressing room), but his decision to play it straight comes at the cost not only of his humorbut his overall cleverness. As is reflective of youth culture at the time, if he were any more painfully earnest, we would only see him crying an Iron Eyes Codependent mono-tear over the river of deceit and betrayal that runs through Collinwood.

So he's growing up. That's a bookend. He's decided to take life seriously. That's a bookend. And he is desperate to stand up for his father, who is getting railroaded on false charges. It feels like he has earned the right to do this. “He” began as a character all too eager to see his father railroaded over allegations the paternoster projected onto, well, who knows? Maybe his other dad. I think we've all had those thoughts. Whether he's doing it for reasons of malice, reasons of justice, reasons of love, or as a five-dollar menu combo of lovingly malicious justice, the David Henesy character begins and ends as someone trying to align his father's legal standing with reality. And it's refreshingly uncynical that he should go from a boy trying to get a guilty father convicted (or at least in hot water) to a kid trying to get his father out. Of course, the two fathers are vastly different. The primary similarity is that the mothers are either physically or emotionally absent, and neither have his best interest at heart. But he is the only person at Collinwood who has yet to see family as more of a mess than a bastion, and so he sticks by the institution with admirable loyalty.

And Samantha does get up on the stand. Of course, she does the opposite of what Tad wanted her to do. She’s ready to betray Quentin with zesty abandon. But The Henesy’s not around for that. It's almost as if this last blast of optimism collides head-on with one final betrayal from an untrustworthy mother. And perhaps that's all that the David Henesy figure can take. He disappears after that. The message? Very few parents are what they appear to be. Especially mothers. Eventually, that destroys the child within.

Dark Shadows teaches its lessons in cycles. Moral development in Collinsport is not a straight line. It's a corkscrew, both moving forward while covering the same ground over and over again. The sometimes surrogate mother figures in this character's life have been fire demons, completely absent, suicidal alcoholics, reanimated occultists, and at last, an untrustworthy shrew. As much as the show is meant for women, the female figures that David encounters, no matter the name, have stunningly little to recommend them. Although Victoria is hired to be his companion, she, like all adults, becomes enraptured by events that pre-date David. In that case, for nearly two centuries. Who can compete with that? Carolyn is likewise lost in a hopelessly lost romantic union, which generally makes her lousy conversation. Liz is obsessed with death whenever John Bennett wants a vacation. And Maggie is at Windcliff. So much for female nurture in Collinsport. Fortunately, for someone with a sniveling, cowardly, alcoholic louse of a father (at least for the first year or so), David finds his modeling and nurturing in the men in his life. At various times, Barnabas, Quentin, and Tom Jennings all follow in Burke Devlin's footsteps to provide David with good advice and understanding moral support. At a time when most male relationships on television were based on macho buffoonery, this is revolutionary and refreshing. If you could take anything away from the David Henesy character, it’s that three uncles can make a hell of a mother.