By DANNY REID

“We don’t think of ourselves as monsters.” - Edward Cullen

The first time I ever heard of TWILIGHT was, of course, from a girl. “Oh, it’s cool,” she explained. “It’s a book series about vampires who live in Washington because it’s cloudy all the time. And they fight, like, werewolves.” Which, indeed, did sound cool, in a ‘some dude felt that HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN wasn’t enough’ fanfiction-y sort of way.

The second time I heard of TWILIGHT was on the internet. Perhaps you’ve heard of the place? It’s an echo chamber, mostly, where every man is a boy and every woman a princess — or a cunt, depending on whether she opens her mouth in disagreement or not. The pushback against the TWILIGHT books is legendary, a massive confluence of armchair feminists and white knights who were utterly terrified of the idea of prepubescent girls reading the sexy story of a sexy vampire and finding its tale of preferable virginity to violate sacrosanct laws of newly won cultural female freedom.

A few years after the series’ final entry and it’s been tossed into the collective trash bin of cultural history, an embarrassing blip. The ship of the cinema state has eagerly given the audience the correctly maternal Katniss Everdeen of THE HUNGER GAMES and second banana Black Widow in the immense AVENGERS dirge — a badass assassin who has never been put at the front of her own entry, less fanboys piss their camouflage shorts at the thought of empathizing with a protagonist who isn’t white and male.

Bella Swann, the heroine of TWILIGHT, is an aberration then and now, a twitchy woman protagonist from the Daria-school of snarky outcasts whose sheer passivity seems to attract friends and admirers in spite of herself. That’s because she’s easy prey, a bundle of insecurities that allows everyone around her to project their wants and desires — including, of course, the audience themselves.

This evolves as the series grows, though. Those who see Bella as an easy mark soon find the situations reversed. Her angst-ridden high school classmates who try to fuck her or out-maneuver her soon rely on her for advice, which is flawless. The vampire boy who finds the scent of her blood irresistible must resist because she tells him to—not unless he’s willing to put a ring on her finger. And the werewolf boy with the puppy-love crush finds in her his Lady MacBeth who urges him to grow up, take responsibility, and be the leader he must be ... and it doesn’t hurt that it will further her own means.

Bella’s journey through the films is from a lost girl wrapped in a blanket of melancholy to becoming the one of the most powerful creatures the world has ever seen—with a perfect little family to boot. She manipulates her way to this, using both her sex and savvy to dominate the weakening structures of the patriarchy, evidenced by her sheriff father’s ineffectual grasp on the small community of Forks, Washington, and the centuries-old structure of the vampire clans, weakened by incest, bloodlust, and general rigid tyranny.

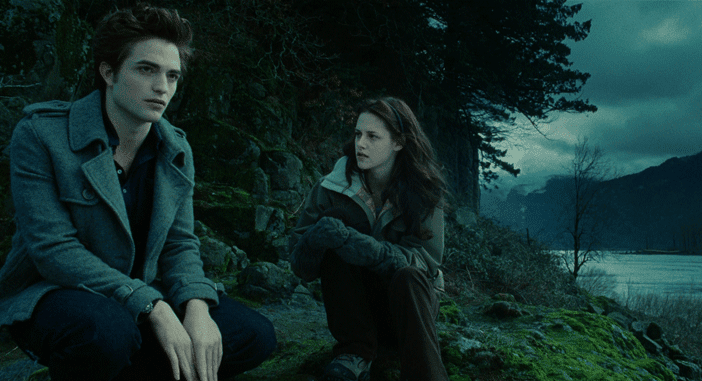

Much of the criticism for the series, besides the fact that 75 percent of the film’s content is that dreaded “people talking about their feelings” thing, comes from Edward Cullen, a big hunk of pale Muenster cheese whose skin sparkles in the sunlight rather than explode. He’s brooding and pouty, but wears trendy clothing and lacks any sense of menace. While he can punch another vampire’s head off, he doesn’t project much beyond a calm sensitivity. Because of Bella’s craven desires, he spends most of the five movies terrified of himself.

It reverses the usual vampire’s seduction. Even Edward, the impossibly gorgeous killing machine, has completely lost his masculine independence as the weakest link in the vampire food chain. Bella can help him and his brood rediscover it, but at a price.

The first TWILIGHT sets up this dynamic swiftly and quietly. Bella is the new girl whose curiosity lands her in a den of bloodsuckers. But they’re the good guys. The bad guys are the roaming vampire gang who smell Bella’s delicious (nigh irresistible) blood and make her a target.

The film is about being watched and desired. Infatuation and the vaguest hints of lust lurk around every corner. Bella is mostly a blank slate in the first movie, wandering around wide eyed and impossibly moored to her own past as an innocent little girl, almost unwilling to leave the safety of the world she once knew until being violently thrown from it. Step one of the hero’s journey over, now it’s time for her to explore and conquer the new reality.

NEW MOON is about the dangers of obsession, on both ends of the equation. Bella and Edward separate after a disastrous party, and we are shown romantic love without its usual gilded Hollywood angle. Rather than longing looks at the stars or delicate evocations of poetry, romantic love in the series is grotesque and unbearable. It’s an ode to deep teenage fatalism with as little window dressing as possible.

Bella also spends far more time with Jacob, a brooding werewolf who feels that the fact that he’s not among the murderous undead would perhaps put him higher in the ‘sleep with Bella’ line than the cold, meek Edward. But while Jacob has absolutely ludicrous pectorals (shown off both early and often), he lacks Edward’s strength and icy charm. And, of course, immortality.

Through their adventures in this go-around, Bella meets the ultimate tools in the patriarchy’s closet, the wizened council of vampires who are, naturally, effeminate (and campy) to a fault. Their henchman is a butch Dakota Fanning who gets to glower at people like a champ and zap them with pain rays or something. Bella has found the enemy, and, despite their powers and reach, they are weak.

The third film, ECLIPSE, is a negotiation. The ending marriage proposal in NEW MOON is clarified and reconsidered, with a bargaining between Bella, who wants to be an immortal undead vampire with all of its benefits, and Edward, who views the act of doing so with paternal condescension.

The confrontation between Edward and Jacob is one of the more electric moments in any of the films, an ideological crossroads for two very different kinds of monsters. The rivals debate their roles and powers, and how that would work best for Bella’s future. Some may see it as a bartering for Bella as property, but the crux of the scene is how both men admit they’re weak where Bella is concerned. Whatever she demands, they shall obey.

The unspoken gnarly racial disharmony that runs through the series comes to a head here, too. The films, one of the few to use Native American characters in any significant way in the last twenty years let alone as sex symbols, frame the rivalry between the encroaching Old World vampires and their sensitive warm blooded werewolves as an unresolved colonial resentment. Jacob and Edward are part of a new, younger generation whose affection for Bella allow them to find common cause for a truce. Love conquers all, it seems.

The first BREAKING DAWN is the best movie in the franchise. The opening half of it, featuring a cheeky montage of Bella eagerly trying to lose her virginity to her new husband, Edward, is possibly the series at its most playful. Indeed, much of the movie (and much of the series) can best be summed up in this clear HOW EDWARD GOT HIS GROOVE BACK scenario where an eager woman rips the bodice off the unwilling vampire and teaches him anew the pleasures of the flesh.

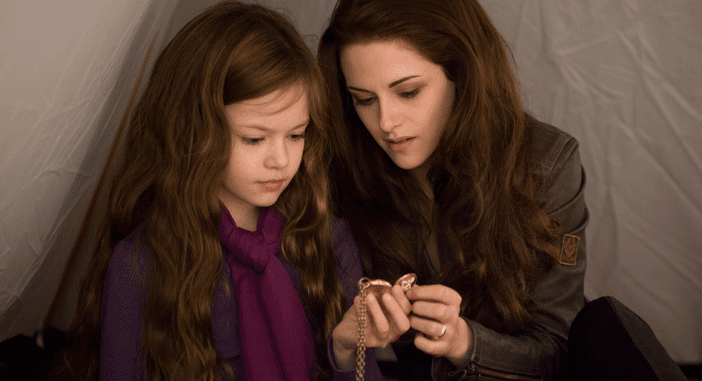

The second half of the movie, which involves an unplanned pregnancy and the threat of all out vampire war climaxes in the birth of Bella and Edward’s unholy vampire baby. The scene is both intensely physical and utterly unique. Few people would have guessed that a vampire performing a caesarian section on a woman with his fangs after their super powered baby broke her spine while still in the womb would somehow be the pivotal scene in a mega budget franchise picture only a few years earlier. Hell, it’s hard to believe just a few years later.

The film also contains one of the series’ creepiest moments (aside from the one mentioned in the last paragraph) where Jacob ‘imprints’ on Edward and Bella’s daughter, thus setting up, yes, one of the film’s major characters to lust after a baby. The movie desperately tries to soft peddle this situation inherited from the books, but combined with Jacob’s brash egotism and forceful crush, the creep factor can’t be ignored.

But that’s also a part of the movies’ charms. Many people view them as merely romances with vampire window dressing, but they clearly set out to horrify the audience as well. Bella’s birth is terrifying. Jacob’s sudden veering into pedophilia is equally unnerving. We see tour groups maimed, a child vampire murdered, and plenty more for the sick thrill of understanding how fucked up all of this stuff is. But, while these characters exist in a world filled to the fringes with the occult and horrific, sex may be the most deeply confusing thing to everyone, with only Bella truly understanding what she wants or needs throughout.

The second BREAKING DAWN is more conventional and far less interesting, though it does contain one of the series more inspired moments. It mostly revolves a lot more action and special effects—something the filmmakers seemed desperate to inject into the series, hoping that a reliance on CGI will give the movie the proper appearance for what turned out to be a summer blockbuster franchise.

The finale involves groups of X-MEN-esque vampires defending Bella’s baby from the legion of the vampire council, with a massive battle in which several series regulars are brutally murdered. Because that didn’t happen in the book, however, the movie backs down and reveals it as a dream sequence. The vampire council, seeing that they don’t have much of a chance to win, decide to let Bella and her many, many defenders live on peacefully.

The moral would seem to be that ancient evil cannot be defeated, only shown to be impotent. Even after acquiring all of her power, Bella remains but one cog in a machine, but she has everything she’s wanted, and like King Conan sitting on his throne, one is left to imagine that the end of the vampire council is merely the story for another day.

|

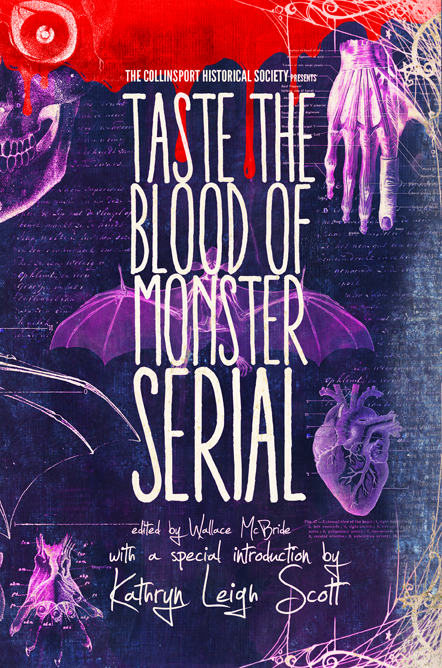

| This essay is one of dozens featured in our new book, "Taste the Blood of Monster Serial." |

The TWILIGHT backlash wasn’t completely without merit, either. Dozens of television shows and movies moved to cash in on its monster mash mythos, with many taking potshots at the series while showcasing a new generation to their hipper, cooler vampires. The stench of the garbage post-INTERVIEW WITH A VAMPIRE films of the late 90s and early 00s, which included detritus like DRACULA 2000, VAMPIRE IN BROOKLYN, QUEEN OF THE DAMNED, the inconceivably awful UNDERWORLD series—oh god, I could spend another 1,000 words just listing all these pieces of shit—and much more were eradicated, and fantasy had its heart pumping anew.

The TWILIGHT saga remains an outlier in the middle of two decades of explosion-laden, inert male teenage fantasies. It’s an utterly bizarre reinvention of the vampire mythos that managed to jar pop culture into remembering what’s so sexy about vampires—the sex!—while flirting with a distinctly un-Hollywood means—the pleasure and power of virginity. The complete aberration of the TWILIGHT series’ success, an odd movie series full of high drama and an utterly unique take on female empowerment in a world steadily arguing for the same blockbuster movie being remade every year, should be celebrated.

DANNY REID lives outside Tokyo, Japan, with his lovely wife and two yappy dogs. He blogs bi-weekly at pre-code.com, a website dedicated to Hollywood films from 1930 to 1934.